reflections on 2025

Not sure what this is? Just check out the idea issue.

Catching Up

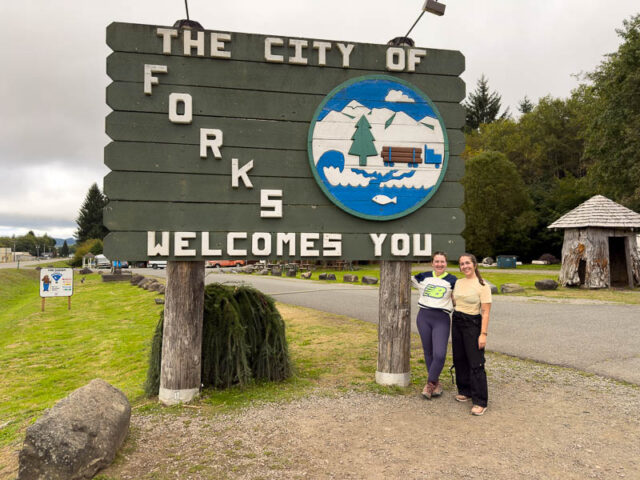

2025 was an eventful year. I did a lot of cycling, a little canoeing, and many hours of Machine Learning coursework. Emily and I played in a mixed doubles tennis league, traveled to Japan for the first time, visited Tennessee, checked Olympic and Crater Lake off our National Parks list, and shared some great times with our friends in San Francisco. Despite all we were able to do, coursework dominated the majority of my time and mental space for the year. This spring I plan to spend more time training for climbing and cycling, traveling locally/domestically, connecting with friends and family, and developing my creative hobbies.

But this newsletter is about looking back. Here is just one highlight from the year.

Over the last two years I have really enjoyed building up and riding old bikes. In 2025 I built some fitness, explored more of the city, and rode a lot of trails across the bridge in Marin where mountain biking originated.

The Bay Area Tour of Microclimates was by far my favorite ride of 2025. Over the course of two days in June I rode through coastal headlands, hilly grasslands, rocky shrublands, and redwood forests. This was actually my second attempt at the route, and I wasn’t planning on doing the full thing. The first time I had to bail near the halfway point, which happens to be Pantoll Campground. I had both muscular and mechanical issues, so I camped there and bummed a ride home the next morning from my friend Zak.

This time I had planned to just stay at Pantoll and then ride home from there the next day. But, fueled by better fitness and riding a much nimbler bikepacking setup, I arrived there by 1pm, several hours earlier than planned.

I took a break, enjoyed a nice view of the Farallon Islands, filled up my water, and decided to continue on. “Don’t stop when you have tailwinds,” was the gist of my thinking. So I continued to climb until I reached Bolinas Ridge and made the descent over rough terrain (especially on a loaded rigid bike) to Samuel P. Tayler State Park and Campground.

I hung out with some other cyclists at the designated hike-in/bike-in spot and then got the best sleep I could. The next day would be a long and exhausting return home over some isolated and rocky but beautiful trails. Riding triumphant back across the Golden Gate Bridge near the end of my adventure, my rear tire went flat. Lo and behold my spare inner tube was also no good, so I ended my journey with a 2-mile bus ride back to the apartment, arriving just minutes before the smash burgers and fries I had Door Dashed.

In 2025 I spent a lot of time modifying a 1998 GT Edge road bike that I bought from an older gentleman in Sacramento who was thinning out his collection. I drove for a total of about 3 hours for the bike because it’s a very special frame. This one was made with Reynolds 853 steel tubes and fillet brazed by hand in Longmont, Colorado. They were mostly made to order, so only 100-200 were built each year for only a few production years. Mine came equipped with an Ultegra groupset with race gearing; that’s not ideal for a newbie road cyclist tackling the San Francisco and Marin hills. It also had a pretty sweet bullhorn handlebar and downtube shifters, which I ditched for traditional drop bars and some nice old Dura Ace STI shifters from eBay. You’ll see those bullhorn bars again though!

The GT Edge originally came with a GT-made carbon fiber front fork, but I was a little nervous riding a 27 year-old third-hand carbon fork. A local bike shop (literally a block from my apartment) sold me a cheap steel replacement from their hoard of project bikes which I promptly spray-painted black and installed. Eventually I’ll get a nicer race-style fork, possibly custom made, but this will do for now.

Before I could really ride I had to modify the drivetrain. I just couldn’t handle the hills with the gear ratios it had, so I got a wider range cassette and tried a few rear derailleurs with my used Dura Ace shifters until a kind stranger on reddit pointed me to the right one (Shimano Alivio) and explained the intricacies of pull ratios. Once I installed that derailleur, I was shifting smoothly and flying both up and down hills. I also learned how to remove/install headsets and bought my first pair of clipless shoes.

I have a few more upgrades in mind, but I’m happy that this bike is finally ready for some serious road mileage over the bridge.

Check out some photos of my bikes, Japan, home, and Olympic.

Thinking Deeper

Attention is Under Siege by Profiteers

I made that claim in the last newsletter. Everyday billionaires battle for your attention. Our collective attention is bought and sold by these profiteers to drive what Nobel Laureate Herbert A. Simon coined the “attention economy.” The attention economy didn’t just spring up out of nowhere, so how did we get here? Tim Wu answers that exhaustively in The Attention Merchants. So what are they?

The Attention Merchants

The fight for our attention is not new. According to Wu, the modern Attention Merchant can be traced back to the 19th century snake oil scheme men and the penny newspapers. The snake oil salesmen relied on entertaining and outlandish claims about their products to capture attention and make sales. The penny newspapers were something like an old-time TMZ. They sold very cheap by publishing scandalous and often unverifiable gossip and selling advertisements. They were not the first ad-based business model, but they may have been the first to use ads to provide a cheap or near free “service.” They represent a shift from providing a valuable service (like investigative journalism) in exchange for money to providing cheap entertainment at virtually no cost to the consumer except their time. That is not really a problem because even scandalous black and white text becomes boring pretty quickly, and no one could really waste that much of their time on it.

Let’s jump ahead to World War One. Europe is in chaos, and the British need troops. A lot of troops. As Americans know well, compulsion doesn’t have the best results for military recruiting, so they needed to mount a campaign to persuade British men to voluntarily join the fight and put their lives on the line. The government Attention Merchants ended up putting together one of the most successful military recruitment campaigns in history, so successful that their propaganda later served as a model for Adolf Hitler. It also got the attention (ha) of the twentieth century ad-men like Edward Bernays who built their campaigns based on psychology.

After this, advertising completed its shift from merely providing consumers with useful information about products. Attention Merchants found they could sell much more if they constructed narratives about the products and companies to actively and increasingly subconsciously persuade consumers to buy. Tobacco companies like Lucky Strike truly mastered this with slogans like “Reach for A Lucky Instead of A Sweet” to target women.

At the same time that advertising strategies shifted from information to persuasion, new technologies began to increase advertisers’ access to consumers. Radio brought them into the home where they could sell narratives to entire families, though usually only for an hour or so each night.

Then came television and the magic of an audio-visual medium. The invention and ubiquity of the television would have far-ranging effects on society and culture which we’ll get into at another time. For now, you can just imagine the advertisers salivating over the money they were about to make by making children salivate over sugary cereal. Television advertising actually became so unscrupulous that people stood up to it and demanded laws to regulate advertising to children. Still, the Attention Merchants adapted and persisted.

Now in the 21st century they ride along in our pockets each day and camp out in our bedrooms in smart home devices, collecting our data and reshaping our behavior.

Advertising has come a long way since the days of merely providing information about a product so that a consumer can make a good decision. Up until fairly recently advertisers had to be content with a mostly one-way interaction with consumers. They had to carefully craft their messages and send them out into the void, attaching them to the most attention-grabbing media they could find and hoping for the best. They built brand-names. They showed how their products could solve problems, often convincing consumers that problem existed in the first place.

But those strategies were limited, and despite the eventual development of a few metrics, they never really knew how effective their advertising was.

Television ratings offered advertisers their first glimpses of attention metrics. They could get an idea of where to target their ads. By this point the Attention Merchants were doing about as well as they could hope. They had survived a couple of close calls and rebranded themselves each time to come out stronger. But they seemed to have found their natural limit with semi-targeted ad campaigns based on generally popular and sensational content.

Then the internet picked up steam, and a little company called Google came along. They had an amazing page-rank algorithm for search but no way to earn money. They were just poor nerds. Eventually, reluctant but desperate, they turned to advertising. In doing so they ushered in a new age and became the first of what Shoshana Zuboff would name Surveillance Capitalists.

You see, the internet offered bi-directional interaction with consumers. Clicks. Google and others began to realize the true potential of the data they could collect through their services. They set about the task of scientifically measuring and optimizing ad performance. Consumers, soon to unironically be called users, never stood a chance.

Google was clever. Though it worked closely with advertisers and began generating massive profits, it didn’t advertise the often sneaky and unethical business practices in which it began to engage.

At this point the Attention Merchants evolved into something more menacing and potentially catastrophic: Surveillance Capitalists.

The Surveillance Capitalists

This term was coined by Shoshana Zuboff in her expose The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. The book landed awkwardly somewhere between cultural idea book and rigorous Marxist academic work. It didn’t fully succeed as either, but it nonetheless introduced some concepts, terminology, and assertions that are essential for understanding where we stand against the tech companies making trillions on ad revenue.

Surveillance Capitalism is an economic sub-system that exploits consumers’ use of technology that tracks them and collects their data. That data is sold, used to build predictive models for individualized marketing, and used to modify consumer behavior to benefit those in control of the data. Zuboff describes the process as an extractive one in which our attentional resources are mined by these companies and sold for profit to our detriment.

Here we dive headfirst into the 21st century alongside Google. They’re doing pretty well by 2006 when a little startup called Facebook starts to pick up steam. These are the companies to which Zuboff (maybe ironically) gives most of her attention. Then, in 2008 the last piece of the puzzle arrived. Enter the innocent and well-meaning iPhone. The smartphone enabled ubiquitous internet access for users and enabled ubiquitous user access for Surveillance Capitalists. Since then, this access has expanded massively through the proliferation of connected ‘smart’ devices, the Internet of Things. All of this is billed as progress and a major boon for humanity.

Let me propose a question. Who benefits the most from “free” internet “services” like Google Search and Facebook? I’ll give you a hint; it’s not you. Nor is it society. The company providing the service and their customers benefit most. The more time we spend on their platform, the more data we generate for them, the more money they make. It’s always about the money.

So what, according to Zuboff, is the strategy of a successful Surveillance Capitalist? First, they have to collect as much data about you as possible. Zuboff calls this data “behavioral surplus”. It is generated simply from your use of internet services and collected via cookies and other tracking methods.

Second, they have to reformulate that behavioral surplus into a marketable product: predictive models. That is, if they can predict who will be mostly likely to click on an ad for a specific product and therefore target those people with ads for said product, they can charge a lot for those ads.

Third, they have to use their behavioral surplus and predictive models to modify their users’ behavior. As kind of a dumb example, imagine you have just searched taco recipes earlier in the day. Now, near dinner-time, you’re walking home and plan to stop at the grocery store on your way. Google, who tracks your location from your phone, sends you an alert that Chipotle is offering 20% off their taco meal. And look at that, uncoincidentally there is one just up the block, so you go there instead of the store. Your behavior has just been modified.

Lastly, they have to convince you that all of this is good for you. They have to brand themselves as progressive companies that are building a better future for humanity. Anything negative gets swept under rug or labeled as collateral damage to be accepted in the inevitable progression of technology.

This has some crucial societal drawbacks which we’ll get to later. For now, we will diverge from Zuboff and pick up some more digestible sources to understand how all this works. We’re just focused on the how.

How does Google extract, predict, and modify our behavior? And how do they paint it positively?

First, they involve themselves in all of your everyday technology. Your email, documents, calendar, photos, contacts, and web browser (Chrome) all provide Google with valuable behavioral surplus. They know you better than your parents and your partner. Unlike social media companies, they are not exactly obsessed with drawing your attention to one product but more interested in providing every digital product that you might need to use throughout the day.

How they use all this information is less well known than the fact they do use it. Certainly they use it for delivering well-timed personalized ads. These days with proprietary LLMs, it’s clear that their very impressive models were built off of collected and scraped data as well. How far Google will go to get your data, and exactly what they use it for is all kept secret with probably more protection than military nuclear information. They have occasionally been caught in their maleficence though. For example, in 2010 investigations revealed that Google was using Street View cars to collect communications, financial data, and other personal information from the Wi-Fi of private addresses.

How could Google be so loved after having its sketchiness completely outed? Great PR. They first deny and refuse to cooperate with government investigations. This is their stalling tactic. For small infractions it works well, and the investigations falter after pubic attention moves on. For the big stuff, they have to get a little more creative. For instance, the Street View debacle was pinned on one unidentified engineer to be dealt with internally (right, right) who allegedly implemented the data collection on their own without instruction (sure). Thanks to the rapid news cycle and short attention span of the public, Google paid some minor fines and came out unscathed from an incident that could have ended smaller companies. By handling situations in this way and implementing new tech before regulation can catch up, Google has from the start acted above the law. Better to ask forgiveness than permission right?

I can’t really go into more detail in this short essay, but if you want to learn to more about why Google actually really sucks, I would recommend reading Zuboff’s book. We’re moving on to a slightly different beast: social media.

Unlike Google, who has a hand in every digital product we need, social media platforms have to convince us to use them. So how do they keep us hooked?

Nir Eyal answers just that question in his book Hooked which is essentially the textbook on how to make software as addictive as possible. After playing a major role in the development of addictive services, Nir later wrote a book called Indistractable about how we as individuals can “hack” back our attention. It’s difficult for me not to read this follow up book as Eyal’s argument that he is not at fault for the negative effects of social media on us all. To him, anyone who struggles with media addiction is just weak-minded and hasn’t learned the right strategies to cope with technology.

Adam Alter offers a different perspective in Irresistible, which describes the strategies used by Meta, Twitter, Google, and others to maximize the amount of time we spend on their platforms. Notably, most of the techniques he describes have been in the employ of the gambling industry for decades. Alter quotes the ex-Google design ethicist Tristan Harris to say “the problem isn’t that people lack willpower; it’s that ‘there are a thousand people on the other side of the screen whose job it is to break down the self-regulation you have.’”

If you really want to follow this stuff back, read up on B.F. Skinner who is known as the father of behaviorism. His work focused on operant conditioning, learning how we as animals respond to stimuli. BJ Fogg was a Stanford professor and one of the first to consider how to use Skinner’s behavioral conditioning studies to influence behavior with technology. He was the teacher of Nyr Eyal and others who went on to design the interfaces and algorithms that glue our eyes to screens.

So how does social media optimize for attention? They work on our subconscious, particularly the drive and reward systems of our brains. Here’s a very simple explanation.

Humans evolved to seek novelty, especially when faced with boredom. This seeking would eventually lead to some reward like food or resources. Skinner proposed that behaviors become associated with a stimulus and can be reinforced by rewards or punishments. For example a light turns on. Eventually, a rat (maybe bored) presses a lever next the light, and food is given. This happens a few more times. Now, anytime the light turns on, the rat will press the lever. Again, food is given. The light is the stimulus. The lever-press is the response. The food is the reward and reinforces the response to the stimulus. Skinner discovered that the strongest way to reinforce a response is to offer the reward on a variable schedule. That is, once the rat begins to expect the food, you don’t give it to them every time they press the button.

This idea is implemented in nearly every social media platform. Likes and comments are doled out as little social status rewards. The notification from the app is a stimulus. But the simple act of turning on your phone screen also becomes a stimulus associated with the reward. Tapping into the app and checking your likes, or scrolling for some funny or emotionally charged content is the response. Receiving positive social feedback in the form likes and views or watching some entertaining video is the reward.

Some other tactics include feedback loops, infinite scroll, and emotion hacking. Emotion hacking is partially engineered intentionally, partially just the outcome of implementing algorithms that maximize user engagement (time) on the platform. For more detail on that, I would highly recommend Adam Alter’s book and also Ten Arguments to Delete Your Social Media Accounts Right Now by Jaron Lanier.

This is how social media hooks us and collects our attention. They have convinced us that their platforms are essential for connection and free information. They are not. As any good Surveillance Capitalist must, they then transform and sell our data while modifying our behavior on a global scale.

This system wasn’t necessarily adopted from greed or maliciousness, though in some cases you could make a strong argument. Johann Hari points out in Stolen Focus that the ad-based business model simply demands optimizing for attention. At this point I feel that I should make a quick note about the employees at Google, Meta, and other companies engaged in surveillance capitalism. While I believe that the business model of these companies has net negative impacts on society, by no means do I blame individual workers who make their living at these companies. Their leaders may be another matter.

I’ve tried to focus on what is happening and how in this essay. How the Profiteers battle for our attention. The war for our attention has been a long one with many twists and turns from snake oil scheme-men to the rise of attention conglomerates like Meta. It has been tightly interwoven with each technological development of new media like radio and the internet, and as we shape our technology, it shapes us right back, sometimes in uncontrollable and unforeseeable ways.

However, the Profiteers are not the only reason for our suffering and shortening attention spans in the 21st century. In the next essay I will discuss how our attention is also under siege by our environment.

A Note about ICE

I’m sending this newsletter out during an especially turbulent time for our country, and it feels irresponsible to not address it. I will be direct. Trump and ICE are perpetrating acts of domestic terror, employing the same strategies that fascist leaders have used in the past to consolidate power and beat nations into submission. Masked secret police who can search and detain without warrants are undemocratic and violate our CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS. They are murdering Americans. These are facts regardless of your opinions on immigration. I’m happy to discuss these issues further in person or on the phone.

Thanks for reading, and feel free to contact me or subscribe.